A student once asked Derald Swineford why he chose art as a career, and the artist said, “I wanted a profession that would not be made off of someone else’s misfortune. I wouldn’t want to be a doctor or a lawyer. They depend on someone else’s problems. I’m in the nicest profession because nobody has to have what I do.” It’s with this gentle simplicity that the artist taught, created, and thought.

A student once asked Derald Swineford why he chose art as a career, and the artist said, “I wanted a profession that would not be made off of someone else’s misfortune. I wouldn’t want to be a doctor or a lawyer. They depend on someone else’s problems. I’m in the nicest profession because nobody has to have what I do.” It’s with this gentle simplicity that the artist taught, created, and thought.

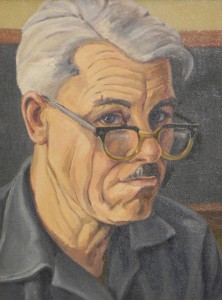

As head of the art department at the Oklahoma College for Women, later to be the University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma, for 30 years and Professor Emeritus for an additional 15 years, Derald Swineford taught thousands of art students. Swineford’s feelings on such an exhaustive number of students: “We had fun. We really did.”

This fun was not only visible in his teaching but in his art as well. Swineford truly enjoyed art as a form of relaxation and entertainment. When asked a price on one of his works, the artist was quite likely to reply: “I’ve already been paid for that.” He once said about art, “It’s my entertainment. It’s my golf.”

Swineford was a self-proclaimed regionalist and with this in mind he attempted to portray the flavor of Oklahoma and the southwestern United States. Not being limited to a single medium, the artist was able to express these regionalist ideas through various outlets. His placid watercolors of the Washita River emerge in striking contrast to his forceful metal statue of the 1960 War Dancer, a work which accents Native American culture.

When it was suggested by a friend that Swineford create a knight from metal, the artist filled the order by depicting a Native American warrior on horseback. “This,” he recalled, “I knew something about” – and knowing about subject matter was important to Swineford. Whether it meant crouching within a Native American war dance to snap a photograph, studying the comparative anatomy of a roadrunner in action or sketching an African zulu princess because he was not allowed to photograph her, Swineford was driven to learn about these models.

Through understanding his subject matter, Swineford was able to invent a wide range of metaphoric symbols. His use of symbolism can be seen in his woodcarving, The Broken Pipe. The idea for this work came to the artist just after the Korean War. Even with the advent of the Southeastern Asian Treaty Organization and the United Nations, Swineford felt that the human values and faiths were still being constantly challenged and broken. In his own words, the artist acknowledged these feelings: “When one caveman met another and they couldn’t agree, they started throwing rocks at one another and that has been going on ever since.”

This thought was the catalyst for The Broken Pipe. The hand grenade at the warrior’s feet represents the peace treaties throughout human existence and the idea that “It’s a safe enough instrument so long as the pin isn’t pulled.” To this Swineford adds: “When someone oversteps a treaty, you have that explosion and it leads to conflict.”

The explosion is depicted by the broken peace pipe and translated by the artist as “the broken faith of mankind.” The skull in the helmet reflects the mortality of what broken promises will do. The warrior with hands held open asks the never-answered question, “What is this thing called peace?”

A native Oklahoman, Swineford was no stranger to the tragic history of the American Indian. Born in Enid on March 10, 1908, Derald Thomas Swineford completed grade school thru high school in his hometown and went on to receive bachelor’s and a master’s degrees in Art from the University of Oklahoma. World War II placed Swineford in West Africa (the Gold Coast and Kenya) with the Army Air Core. This introduced the artist to yet another culture which would add new characters to his portfolio. The war’s end brought Swineford home to his wife, Mary. Together they raised two sons, whose athletic achievements Swineford painted and sculpted. The roots he set down in his native land, along with his family, offered Swineford a lifetime of artistic media.

Swineford may have seen the regionalist within himself, but a significant amount of naturalism exists there also. His landscapes of the college farm are reminiscent of the peace that Swineford found within nature. Many of these are depicted seasonally and generate ideas of a cold winter day, the cleansing of spring, the stillness of an Oklahoma summer, and the color palette of autumn. These year-round landscapes provided the artist with a place to contemplate his favorite pastime, combining the beauty of nature with the skills of his profession. From the dynamics of a mountain sheep in motion to the type of wood from which a dancer should be carved, nature taught Swineford a lot about himself and his trade. These close feelings of nature explain the artist’s comparison of nature being his church.

The snapshot style of animals in action on canvas as well as statuary is another naturalistic quality of Swineford’s. On exhibit is a painstaking rendering of the artists’s own bird dog, Shay. Here Swineford took on the tedious task of cutting and placing individual metal blades of grass below his trusted friend, who is in the act of retrieving a quail. The nature-in-motion idea that Swineford portrayed is seen in another metal sculpture on exhibit, that of a roadrunner screeching to a halt in momentary attempt to perhaps glance at a morsel of food. This action scene is set alongside another metal work, Praire Chicken.

This work is an example of one of the favorite characteristics of Swineford’s metal art, that of the “found object.” Though he most likely would not have admitted it himself, the idea of using found objects for his work placed Swineford in yet a third category, the modernist.

If the viewer takes note of the details in the Prairie Chicken, it will become evident that spoons are used as pouches. In fact, an array of hardware can be found in Swineford’s metal statues. The artist would readily acknowledge using “a handful of this and a handful of that” in order to express himself in metal. Though he most likely used the found object method for practical reasons, Swineford paralleled the modern art world with this “use only what can be found” idea. Swineford believed that as an artist worked with these second-hand objects, their uses would become more understandable. Automobile brake drums, for instance, became a base for many of his Native American dancer statues.

Besides allowing for practical costs on art projects, metal became a favorite medium for Swineford because, as the artist liked to claim, “there is much more artistic freedom through steel as a medium. You can do anything you want with it.” This led Swineford into the study of what is known as “architectonics,” or the stability of freestanding art. Through metal sculpting, Swineford enjoyed the unique ability of minimal need for statuesque support. It gave him a wider range of subject pose, which fit perfectly with his “dancer” statuary, as well as his wildlife in motion.

Swineford reveled in the timeless motion of woodcarving. Wood sculpting was one of Swineford’s favorite pastimes, and it wasn’t uncommon for him to be seen in public with a piece of wood in one hand and a chisel or carving knife in the other. Swineford once said, “Wood is like being a discoverer. Take something off and you’re the first person to ever see it, a treasure hunter.”

While stationed in Africa during World War II, Swineford once carved a statue from a post in a native village. In order to carry this out, the artist had to make his own tools out of broken blades and worn files.

Africa could be where Swineford got the inspiration to use found objects. Besides making his own carving tools, Swineford was limited in drawing media available. In the exhibit are several of his Africa drawings, of which the majority were done in litho pencil and a couple in simple wax crayons. These drawings were created by Swineford in 1943 and 1944 in Africa. Once again, this gave Swineford a chance to learn about another culture. In these drawings, he attempts to give the actual personality of each individual character through facial expression. Proof of his need to know about his subject material is seen in a 1985 video interview, in which he offers the African tribal name of each character without hesitation. Swineford also drew a number of tribal religious sites and dances during his stay in Africa that border on a Cubist-like style that he also most likely derived from that same region.

Much of Swineford’s work characterized the artist himself by reflecting his ability to view things with an outside-looking-in viewpoint. Though not on exhibit, a metal statue of Swineford’s Cello Player reflects this view. Once, while at a symphony, Swineford marveled at the way the cello player must be precariously balanced on the edge of his chair. In the statue, Swineford exaggerates this balance, thus allowing the viewer to have flowing eye movement throughout the work. He especially noted the intense concentration with which this balancing act took place. Even years after the metal sculpture was completed, Swineford would chuckle in amazement at the ability of a person to remain in this seemingly uncomfortable position for any length of time.

It is this “outside the lines” viewpoint that Swineford tried to instill within his own students. As Swineford simply put it, “The fellow who does what he can do, without trying to be too elaborate with what he’s doing, eventually controls it and has fun with it.” He stressed that students should not become discouraged when art is not easy but to follow through with what they believe and what they feel. On this point, Swineford commented that art should be studied but also, “tried out.”

This “trying out” signifies Derald Swineford as a teacher and an artist. Throughout his 82-year lifetime, his many contributions to the world of art were experiments for the artist himself. Swineford’s thoughts on his own art were neatly summarized when he said, “Everything I do is an experiment.” It is this idea that made Derald Swineford an effective teacher , a lover of nature, and an artist completely relaxed with his accomplishments.

~Layne Thrift